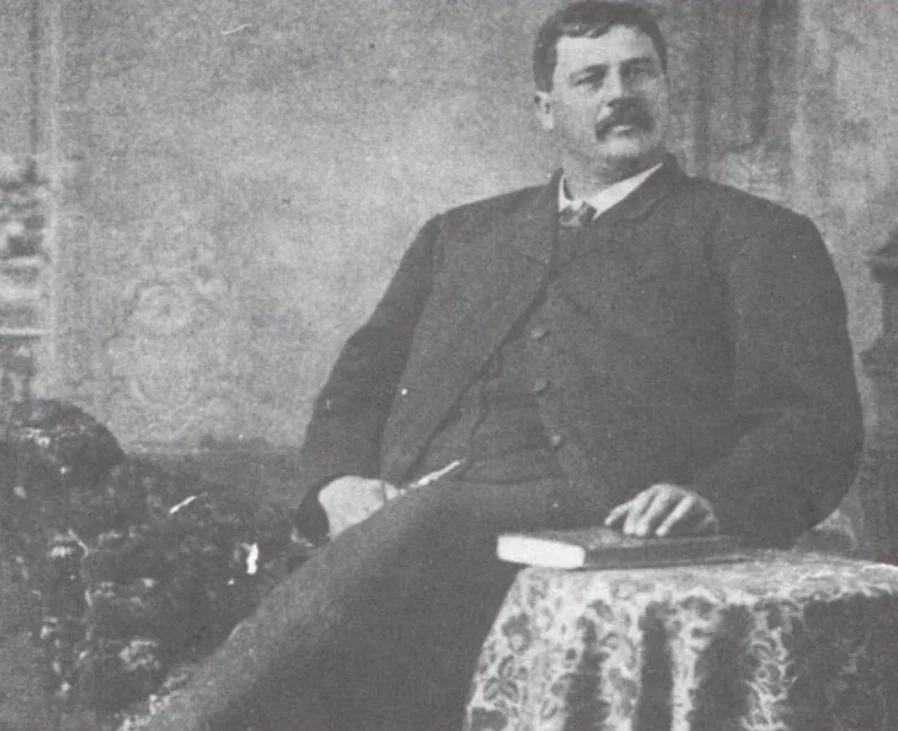

Bill Dunbar

Originally from Bridgenorth, Bill Dunbar became a legend during his years working for Mossom Boyd as a shanty foreman. In the nineteenth century, many young men went north to work for lumber companies in the winter and lived larger than life. The boys in the shanty were notorious jokesters, they loved playing tricks on each other. There are many tall tales of their unbelievable physical exploits to show off. For entertainment they might assemble a ‘brag load,’ having their horses pull a massive load of timbers. To be a great foreman required an ability to play along with the culture of the shanties, while maintaining the respect of the lumberjacks. Bill Dunbar fit right into this world: he loved horses, was a great hunter, a “crack marksman,” and had a reputation for generosity—a heart of gold.

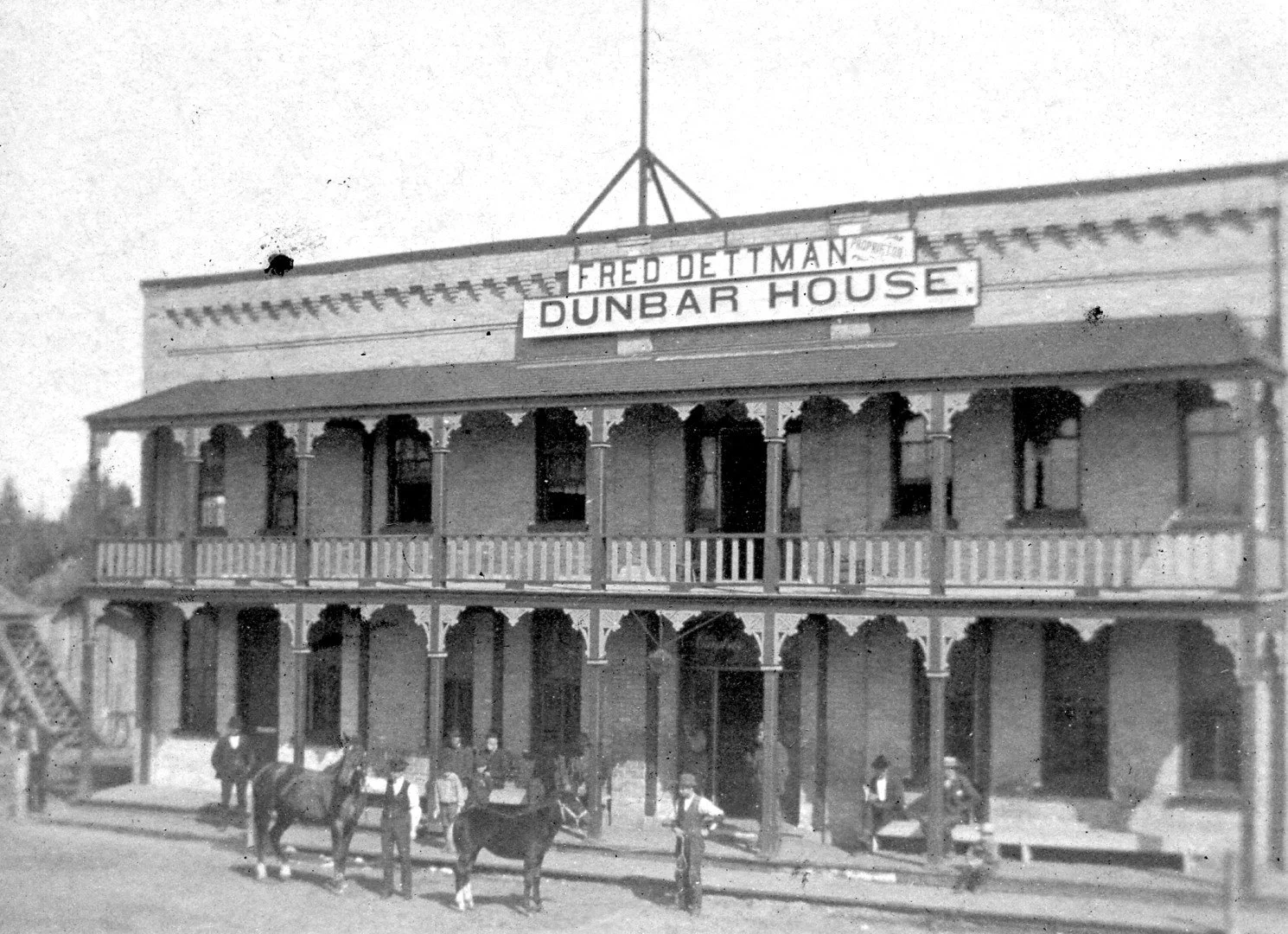

In 1858, the Bobcaygeon Road (similar to modern 49, 121 and 35 from Bobcaygeon to Dwight) opened to fledgling community of Kinmount, providing access to the district. For years, it served as a supply route for the shanties, as many teams headed north bringing lumberjacks and supplies from Bobcaygeon. Bill married Mary Young and operated a hotel at Union Creek that was complete by 1880. Given the rough road conditions of the era, it was often necessary to stop over on the way from Bobcaygeon to Kinmount. Alcohol was not allowed in the shanties (though there were many stories involving hidden whiskey bottles!) and Dunbar’s Union Creek inn was dry. Three years later, he acquired the Victoria Hotel, which was located near where Monck Road from the west met Kinmount’s Main Street. After his hotel burnt in 1890 (taking much of the business section of Kinmount with it), he borrowed $6,500 to rebuild on a grander scale. The new hotel included a bar, restaurant, meeting room, billiard room, sample room (for travelling vendors to exhibit their wares) and stables for 17 horses.

On a winter’s night in 1894, Bill was on his way home from a Peterborough horse race with friend Bob Cottingham. As was the custom in those days, they travelled on the lakes to make the journey shorter. At Gannon’s Narrows their cutter plunged into the dark, frigid waters of Pigeon Lake. The tragic deaths of men and horses reverberated through the community of Kinmount and the logging camps, inspiring Mrs. Cain to write The Drownding of Bill Dunbar, which was put to music by local fiddler Billy Craig. This dirge was sung in many logging camps, as recited by Bobcaygeon’s Joe Thibadeau:

Come all you sympathizers, I pray you lend an ear.

It’s of a drownding accident as you shall quickly hear.

It’s the drownding of Bill Dunbar, a man you all know well—

He lived in the village of Kinmount where he ran a big hotel.

Bill Dunbar was a noble man as you may understand—

Kind-hearted and obliging, a powerful able man.

It made no difference what you profess, he would always treat you well.

There was no danger of being insulted in Dunbar’s big hotel.

They drove down to attend the races, as you may understand,

Returning home all from the same, he and Bob Cunningham [aka Cottingham].

The night being dark, they lost their way, which grieves me to relate:

They drove into Gannon’s Narrows at the foot of Pigeon Lake.

The team was lost, both men were drowned, which is hard for me to unfold,

It being in the depths of winter and the water was piercing cold.

Poor Bill he fought hard for his life, as I have heard them say;

He threw his mitts out on the ice as a token where he lay.

It was on a Tuesday evening they met with their sad doom,

And their bodies were not recovered until Thursday afternoon.

They were taken home to Kinmount; large crowds did gather there—

The people came from far and near when their heard of the sad affair.

Bill Dunbar in his former days was foreman for Mossom Boyd

And many the river he did run, both narrow, deep and wide.

He was never known to send a man where danger would draw near,

But he boldly took the lead himself without either dread or fear.

Bill leaves a wife and one small child in sorrow grief and pain;

Likewise his brothers and sisters in sorrow to remain.

In meditation they are left, which grieves them to the heart,

That it should ever come their lot that he would from them part.

He’s gone the road we all must go, let the time come short or long,

So I’ll drop my pen, likewise conclude my sentimental song,

Hoping to meet on a better shore where trials they are few,

Where we shall return in happiness old acquaintances to renew.